The Phallic psychosexual Stage of Development

(takes place between 3 – 5 years of age)

Little boys and girls start to notice their genitalia and that they are different to each other.

Boys notice that they have penises.

Girls notice that they don’t have penises.

Boys and girls start paying more attention to their biological gender differences.

Their mother is the source of all pleasure and gratification. She feeds, hugs, protects, cares, loves, kisses and comforts them.

The little boys and girls think that their mothers belong to them. They want their mother’s all for themselves. They do not want to share their mother. They feel as if their mother is theirs to have. They feel like they own their mothers.

BUT MOTHERS DON’T BELONG TO THEIR SON OR DAUGHTER!!! THEY HAVE TO GET THEIR LITTLE KIDS TO UNDERSTAND THAT.

This is where the crisis arises!

•As the child gets older, the child notices that the mother is paying attention to someone else.

•In the case of a little boy, he notices that the mother’s attention is not solely focussed on him.

•The boy sees that he has competion!

Here is the conflict!

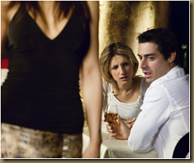

•That competiton for attention is between him and the Father. The boy becomes acutely aware of the fact that the mother is paying a lot of attention to the father. Attention, that he feels HE should be getting – “It’s my mommy!”.

•The boy becomes jealous of the father and starts to get into a competiton with the father for the mommy’s attention and love.

•Freud says that the little boy starts to HATE the Father and wishes to get rid of him so that he may have his mommy all to himself!

(Video 1 and Video 2)

•The boy sees his father as a threat – an enemy! Someone who is trying to take his mommy away from him.

•The little boy enters into a contest with his father. Freud also says that at this stage because of the boys awareness of the biological differences between girls and boys, the boy is also suffering from a great fear that he might lose his penis, and be like a girl. Freud calls this “castration anxiety”. Freud says that when the boy enters into this contest, he after all his efforts realises that his father is the stronger party. He fears that in this competiton to win his mother – the stranger father might cut off his penis and he might end up like the other kind of little person that he has become aware of – A GIRL WHO DOESN’T HAVE WHAT HE HAS.

•So he concedes/gives up and defers to his father, gives up his fight for his mother and joins his father – “If you cant beat them, join them” – he starts copying his father – this is where gender identity is formed, as he emulates the masculine characteristics of his father.

•The mother has to gently show the little boy that she doesn’t belong to him alone. That she must be shared with the father and himself (and possibly other siblings). So in a sense she has to reject him. If she rejects him harshly – two things can happen – as an adult he can become a player (The Ladies Man) or he can become a guys guy (the geek, nerd, bookworm).

•Why? - remember we said that there has to be resolution of a conflict at different stages of development? There is stress – when there is stress we regress to an earlier stage of If the boy receives is rejected harshly – he spends the rest of his life trying to make up, trying to find the attention, win the favour of his mother. He is forever trying to make his mother choose him. The Reality Principle demands that of course he cant have his mother, so the ego sublimates that desire into the pursuit of women.

The Player – (who is the player – examples – Tiger Woods, Charlie Sheen, George Clooney, Simon Cowell – sleeps with as many people as he can, deceiptful, scared of commitment) He can never have real, lasting true relationships with women – because he is scared! He sleeps and tries to get as many women as possible because he is trying to prove to himself, that he is worthy of attention. But he never lets them get close because he is scared that if they do, they might see that same thing that his mother saw that made her choose his father instead of him, and reject him! That will hurt – hurt causes tension. So he never gets close because he doesn’t want to be hurt.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

The Guy’s guy – (who is he) – likes to hang with the guys. Really into sports, games, academic pursuits, reading. Has lots of friends but

Why? He too is scared. He was rejected harshly by his mother . Because of that fear – he avoids all situations where he might be rejected as a male competitor. He doesn’t want to go through that pain again – so he avoids situations that place him in that position.

•Remember we talked about how the boy starts to identify with his father once he concedes? That is because he is rejected by his mother and he has to find a way to stay somewhat in the game, he sees that his father seems to have it all worked out (how to get his mother’s attention) – so he realises that he needs to copy that.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

•

Now if a mother doesn’t reject the boy at all – there is no need for him to identify with the father, so Freud says that that type of boy will identify more with the mother’s femininity. That type of boy as an adult will be more effeminate, be more sensitive, display more feminine personality traits than an average male adult. – The Metrosexual male, kind, senstive, caring, well-dressed, perfect hair, spends time on his look, appearance etc.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Read this funny account by a famous writer Frank O’Connor as he talks about his early childhood battle with his father -

Irish writer Frank O’Connor explains,

far better than Freud might have done ...

My Oedipus Complex

Father was in the army all through the war – the first war, I mean – so,

up to the age of five, I never saw much of him, and what I saw did not

worry me. Sometimes I woke and there was a big figure in khaki

peering down at me in the candlelight. Sometimes in the early morning

I heard the slamming of the front door and the clatter of nailed boots

down the cobbles of the lane. These were Father’s entrances and

exits. Like Santa Claus he came and went mysteriously.

In fact, I rather liked his visits, though it was an uncomfortable squeeze

between Mother and him when I got into the big bed in the early

morning. He smoked, which gave him a pleasant musty smell, and shaved, an operation of

astounding interest. Each time he left a trail of souvenirs – model tanks and Gurkha knives

with handles made of bullet cases, and German helmets and cap badges and button sticks,

and all sorts of military equipment – carefully stowed away in a long box on top of the

wardrobe, in case they ever came in handy. There was a bit of the magpie about Father; he

expected everything to come in handy. When his back was turned, Mother let me get a chair

and rummage through his treasures. She didn’t seem to think so highly of them as he did.

The war was the most peaceful period of my life. The window of my attic faced southeast. My

mother had curtained it, but that had small effect. I always woke with the first light and, with

all the responsibilities of the previous day melted, feeling myself rather like the sun, ready to

illumine and rejoice. Life never seemed so simple and clear and full of possibilities as then. I

put my feet out from under the clothes – I called them Mrs. Left and Mrs. Right – and

invented dramatic situations for them in which they discussed the problems of the day. At

least Mrs. Right did; she was very demonstrative, but I hadn’t the same control of Mrs. Left,

so she mostly contented herself with nodding agreement.

They discussed what Mother and I should do during the day, what Santa Claus should give a

fellow for Christmas, and what steps should be taken to brighten the home. There was that

little matter of the baby, for instance. Mother and I could never agree about that. Ours was

the only house in the terrace without a new baby, and Mother said we couldn’t afford one till

Father came back from the war because they cost seventeen and six.

That showed how simple she was. The Geneys up the road had a baby, and everyone knew

they couldn’t afford seventeen and six. It was probably a cheap baby, and Mother wanted

something really good, but I felt she was too exclusive. The Geneys’ baby would have done

us fine.

Having settled my plans for the day, I got up, put a chair under the attic window, and lifted the

frame high enough to stick out my head. The window overlooked the front gardens of the

terrace behind ours, and beyond these it looked over a deep valley to the tall, red brick

houses terraced up the opposite hillside, which were all still in shadow, while those at our

side of the valley were all lit up, though with long strange shadows that made them seem

unfamiliar; rigid and painted.

After that I went into Mother’s room and climbed into the big bed. She woke and I began to

tell her of my schemes. By this time, though I never seemed to have noticed it, I was petrified

in my nightshirt, and I thawed as I talked until, the last frost melted, I fell asleep beside her

and woke again only when I heard her below in the kitchen, making the breakfast.

After breakfast we went into town; heard Mass at St. Augustine’s and said a prayer for

Father, and did the shopping. If the afternoon was fine we either went for a walk in the

country or a visit to Mother’s great friend in the convent, Mother Saint Dominic. Mother had

them all praying for Father, and every night, going to bed, I asked God to send him back safe

from the war to us. Little, indeed, did I know what I was praying for!

One morning, I got into the big bed, and there, sure enough, was Father in his usual Santa

Claus manner, but later, instead of uniform, he put on his best blue suit, and Mother was as

pleased as anything. I saw nothing to be pleased about, because, out of uniform, Father was

altogether less interesting, but she only beamed, and explained that our prayers had been

answered, and off we went to Mass to thank God for having brought Father safely home.

The irony of it! That very day when he came in to dinner he took off his boots and put on his

slippers, donned the dirty old cap he wore about the house to save him from colds, crossed

his legs, and began to talk gravely to Mother, who looked anxious. Naturally, I disliked her

looking anxious, because it destroyed her good looks, so I interrupted him.

"Just a moment, Larry!" she said gently. This was only what she said when we had boring

visitors, so I attached no importance to it and went on talking.

"Do be quiet, Larry!" she said impatiently. "Don’t you hear me talking to Daddy?"

This was the first time I had heard those ominous words, "talking to Daddy," and I couldn’t

help feeling that if this was how God answered prayers, he couldn’t listen to them very

attentively.

"Why are you talking to Daddy?" I asked with as great a show of indifference as I could

muster.

"Because Daddy and I have business to discuss. Now, don’t interrupt again!"

In the afternoon, at Mother’s request, Father took me for a walk. This time we went into town

instead of out in the country, and I thought at first, in my usual optimistic way, that it might be

an improvement. It was nothing of the sort. Father and I had quite different notions of a walk

in town. He had no proper interest in trams, ships, and horses, and the only thing that

seemed to divert him was talking to fellows as old as himself. When I wanted to stop he

simply went on, dragging me behind him by the hand; when he wanted to stop I had no

alternative but to do the same. I noticed that it seemed to be a sign that he wanted to stop for

a long time whenever he leaned against a wall. The second time I saw him do it I got wild. He

seemed to be settling himself forever. I pulled him by the coat and trousers, but, unlike

Mother who, if you were too persistent, got into a wax and said: "Larry, if you don’t behave

yourself, I’ll give you a good slap," Father had an extraordinary capacity for amiable

inattention. I sized him up and wondered would I cry, but he seemed to be too remote to be

annoyed even by that. Really, it was like going for a walk with a mountain! He either ignored

the wrenching and pummeling entirely, or else glanced down with a grin of amusement from

his peak. I had never met anyone so absorbed in himself as he seemed.

At teatime, "talking to Daddy" began again, complicated this time by the fact that he had an

evening paper, and every few minutes he put it down and told Mother something new out of

it. I felt this was foul play. Man for man, I was prepared to compete with him any time for

Mother’s attention, but when he had it all made up for him by other people it left me no

chance. Several times I tried to change the subject without success.

"You must be quiet while Daddy is reading, Larry," Mother said impatiently.

It was clear that she either genuinely liked talking to Father better than talking to me, or else

that he had some terrible hold on her which made her afraid to admit the truth.

"Mummy," I said that night when she was tucking me up, "do you think if I prayed hard God

would send Daddy back to the war?"

After that I went into Mother’s room and climbed into the big bed. She woke and I began to

tell her of my schemes. By this time, though I never seemed to have noticed it, I was petrified

in my nightshirt, and I thawed as I talked until, the last frost melted, I fell asleep beside her

and woke again only when I heard her below in the kitchen, making the breakfast.

After breakfast we went into town; heard Mass at St. Augustine’s and said a prayer for

Father, and did the shopping. If the afternoon was fine we either went for a walk in the

country or a visit to Mother’s great friend in the convent, Mother Saint Dominic. Mother had

them all praying for Father, and every night, going to bed, I asked God to send him back safe

from the war to us. Little, indeed, did I know what I was praying for!

One morning, I got into the big bed, and there, sure enough, was Father in his usual Santa

Claus manner, but later, instead of uniform, he put on his best blue suit, and Mother was as

pleased as anything. I saw nothing to be pleased about, because, out of uniform, Father was

altogether less interesting, but she only beamed, and explained that our prayers had been

answered, and off we went to Mass to thank God for having brought Father safely home.

The irony of it! That very day when he came in to dinner he took off his boots and put on his

slippers, donned the dirty old cap he wore about the house to save him from colds, crossed

his legs, and began to talk gravely to Mother, who looked anxious. Naturally, I disliked her

looking anxious, because it destroyed her good looks, so I interrupted him.

"Just a moment, Larry!" she said gently. This was only what she said when we had boring

visitors, so I attached no importance to it and went on talking.

"Do be quiet, Larry!" she said impatiently. "Don’t you hear me talking to Daddy?"

This was the first time I had heard those ominous words, "talking to Daddy," and I couldn’t

help feeling that if this was how God answered prayers, he couldn’t listen to them very

attentively.

"Why are you talking to Daddy?" I asked with as great a show of indifference as I could

muster.

"Because Daddy and I have business to discuss. Now, don’t interrupt again!"

In the afternoon, at Mother’s request, Father took me for a walk. This time we went into town

instead of out in the country, and I thought at first, in my usual optimistic way, that it might be

an improvement. It was nothing of the sort. Father and I had quite different notions of a walk

in town. He had no proper interest in trams, ships, and horses, and the only thing that

seemed to divert him was talking to fellows as old as himself. When I wanted to stop he

simply went on, dragging me behind him by the hand; when he wanted to stop I had no

alternative but to do the same. I noticed that it seemed to be a sign that he wanted to stop for

a long time whenever he leaned against a wall. The second time I saw him do it I got wild. He

seemed to be settling himself forever. I pulled him by the coat and trousers, but, unlike

Mother who, if you were too persistent, got into a wax and said: "Larry, if you don’t behave

yourself, I’ll give you a good slap," Father had an extraordinary capacity for amiable

inattention. I sized him up and wondered would I cry, but he seemed to be too remote to be

annoyed even by that. Really, it was like going for a walk with a mountain! He either ignored

the wrenching and pummeling entirely, or else glanced down with a grin of amusement from

his peak. I had never met anyone so absorbed in himself as he seemed.

At teatime, "talking to Daddy" began again, complicated this time by the fact that he had an

evening paper, and every few minutes he put it down and told Mother something new out of

it. I felt this was foul play. Man for man, I was prepared to compete with him any time for

Mother’s attention, but when he had it all made up for him by other people it left me no

chance. Several times I tried to change the subject without success.

"You must be quiet while Daddy is reading, Larry," Mother said impatiently.

It was clear that she either genuinely liked talking to Father better than talking to me, or else

that he had some terrible hold on her which made her afraid to admit the truth.

"Mummy," I said that night when she was tucking me up, "do you think if I prayed hard God

would send Daddy back to the war?"

She seemed to think about that for a moment.

"No, dear," she said with a smile. "I don’t think He would."

"Why wouldn’t He, Mummy?"

"Because there isn’t a war any longer, dear."

"But, Mummy, couldn’t God make another war, if He liked?"

"He wouldn’t like to, dear. It’s not God who makes wars, but bad people."

"Oh!" I said. I was disappointed about that. I began to think that God wasn’t quite what He

was cracked up to be.

Next morning I woke at my usual hour, feeling like a bottle of champagne. I put out my feet

and invented a long conversation in which Mrs. Right talked of the trouble she had with her

own father till she put him in the Home. I didn’t quite know what the Home was but it sounded

the right place for Father. Then I got my chair and stuck my head out of the attic window.

Dawn was just breaking, with a guilty air that made me feel I had caught it in the act. My

head bursting with stories and schemes, I stumbled in next door, and in the half-darkness

scrambled into the big bed. There was no room at Mother’s side so I had to get between her

and Father. For the time being I had forgotten about him, and for several minutes I sat bolt

upright, racking my brains to know what I could do with him. He was taking up more than his

fair share of the bed, and I couldn’t get comfortable, so I gave him several kicks that made

him grunt and stretch. He made room all right, though. Mother waked and felt for me. I settled

back comfortably in the warmth of the bed with my thumb in my mouth.

"Mummy!" I hummed, loudly and contentedly.

"Sssh! dear," she whispered. "Don’t wake Daddy!"

This was a new development, which threatened to be even more serious than "talking to

Daddy." Life without my early-morning conferences was unthinkable.

"Why?" I asked severely.

"Because poor Daddy is tired." This seemed to me a quite inadequate reason, and I was

sickened by the sentimentality of her "poor Daddy." I never liked that sort of gush; it always

struck me as insincere.

"Oh!" I said lightly. Then in my most winning tone: "Do you know where I want to go with you

today, Mummy?"

"No, dear," she sighed.

"I want to go down the Glen and fish for thornybacks with my new net, and then I want to go

out to the Fox and Hounds, and –"

"Don’t-wake-Daddy!" she hissed angrily, clapping her hand across my mouth.

But it was too late. He was awake, or nearly so. He grunted and reached for the matches.

Then he stared incredulously at his watch.

"Like a cup of tea, dear?" asked Mother in a meek, hushed voice I had never heard her use

before. It sounded almost as though she were afraid.

"Tea?" he exclaimed indignantly. "Do you know what the time is?"

"And after that I want to go up the Rathcooney Road," I said loudly, afraid I’d forget

something in all those interruptions.

"Go to sleep at once, Larry!" she said sharply.

I began to snivel. I couldn’t concentrate, the way that pair went on, and smothering my earlymorning

schemes was like burying a family from the cradle. Father said nothing, but lit his

pipe and sucked it, looking out into the shadows without minding Mother or me. I knew he

was mad. Every time I made a remark Mother hushed me irritably. I was mortified. I felt it

wasn’t fair; there was even something sinister in it. Every time I had pointed out to her the

waste of making two beds when we could both sleep in one, she had told me it was healthier

like that, and now here was this man, this stranger, sleeping with her without the least regard

for her health! He got up early and made tea, but though he brought Mother a cup he brought

none for me.

"Mummy," I shouted, "I want a cup of tea, too."

"Yes, dear," she said patiently. "You can drink from Mummy’s saucer."

That settled it. Either Father or I would have to leave the house. I didn’t want to drink from

Mother’s saucer; I wanted to be treated as an equal in my own home, so, just to spite her, I

drank it all and left none for her. She took that quietly, too. But that night when she was

putting me to bed she said gently:

"Larry, I want you to promise me something."

"What is it?" I asked.

"Not to come in and disturb poor Daddy in the morning. Promise?"

"Poor Daddy" again! I was becoming suspicious of everything involving that quite impossible

man.

"Why?" I asked.

"Because poor Daddy is worried and tired and he doesn’t sleep well."

"Why doesn’t he, Mummy?"

"Well, you know, don’t you, that while he was at the war Mummy got the pennies from the

post office?"

"From Miss MacCarthy?"

"That’s right. But now, you see, Miss MacCarthy hasn’t any more pennies, so Daddy must go

out and find us some. You know what would happen if he couldn’t?"

"No," I said, "tell us."

"Well, I think we might have to go out and beg for them like the poor old woman on Fridays.

We wouldn’t like that, would we?"

"No," I agreed. "We wouldn’t."

"So you’ll promise not to come in and wake him?"

"Promise."

Mind you, I meant that. I knew pennies were a serious matter, and I was all against having to

go out and beg like the old woman on Fridays. Mother laid out all my toys in a complete ring

round the bed so that, whatever way I got out, I was bound to fall over one of them. When I

woke I remembered my promise all right. I got up and sat on the floor and played – for hours,

it seemed to me. Then I got my chair and looked out the attic window for more hours. I

wished it was time for Father to wake; I wished someone would make me a cup of tea. I

didn’t feel in the least like the sun; instead, I was bored and so very, very cold! I simply

longed for the warmth and depth of the big feather bed. At last I could stand it no longer. I

went into the next room. As there was still no room at Mother’s side I climbed over her and

she woke with a start. "Larry," she whispered, gripping my arm very tightly, "what did you

promise?"

"But I did, Mummy," I wailed, caught in the very act. "I was quiet for ever so long."

"Oh, dear, and you’re perished!" she said sadly, feeling me all over. "Now, if I let you stay will

you promise not to talk?"

"But I want to talk, Mummy," I wailed.

"That has nothing to do with it," she said with a firmness that was new to me. "Daddy wants

to sleep. Now, do you understand that?"

I understood it only too well. I wanted to talk, he wanted to sleep – whose house was it,

anyway?

"Mummy," I said with equal firmness, "I think it would be healthier for Daddy to sleep in his

own bed."

That seemed to stagger her, because she said nothing for a while.

"Now, once for all," she went on, "you’re to be perfectly quiet or go back to your own bed.

Which is it to be?"

The injustice of it got me down. I had convicted her out of her own mouth of inconsistency

and unreasonableness, and she hadn’t even attempted to reply. Full of spite, I gave Father a

kick, which she didn’t notice but which made him grunt and open his eyes in alarm.

"What time is it?" he asked in a panic-stricken voice, not looking at Mother but at the door, as

if he saw someone there.

"It’s early yet," she replied soothingly. "It’s only the child. Go to sleep again.... Now, Larry,"

she added, getting out of bed, "you’ve wakened Daddy and you must go back."

This time, for all her quiet air, I knew she meant it, and knew that my principal rights and

privileges were as good as lost unless I asserted them at once. As she lifted me, I gave a

screech, enough to wake the dead, not to mind Father.

He groaned. "That damn child! Doesn’t he ever sleep?"

"It’s only a habit, dear," she said quietly, though I could see she was vexed.

"Well, it’s time he got out of it," shouted Father, beginning to heave in the bed. He suddenly

gathered all the bedclothes about him, turned to the wall, and then looked back over his

shoulder with nothing showing only two small, spiteful, dark eyes. The man looked very

wicked. To open the bedroom door, Mother had to let me down, and I broke free and dashed

for the farthest corner, screeching.

Father sat bolt upright in bed. "Shut up, you little puppy," he said in a choking voice.

I was so astonished that I stopped screeching. Never, never had anyone spoken to me in

that tone before. I looked at him incredulously and saw his face convulsed with rage. It was

only then that I fully realized how God had codded me, listening to my prayers for the safe

return of this monster.

"Shut up, you!" I bawled, beside myself.

"What’s that you said?" shouted Father, making a wild leap out of the bed.

"Mick, Mick!" cried Mother. "Don’t you see the child isn’t used to you?"

"I see he’s better fed than taught," snarled Father, waving his arms wildly. "He wants his

bottom smacked."

All his previous shouting was as nothing to these obscene words referring to my person.

They really made my blood boil.

"Smack your own!" I screamed hysterically. "Smack your own! Shut up! Shut up!"

At this he lost his patience and let fly at me. He did it with the lack of conviction you’d expect

of a man under Mother’s horrified eyes, and it ended up as a mere tap, but the sheer

indignity of being struck at all by a stranger, a total stranger who had cajoled his way back

from the war into our big bed as a result of my innocent intercession, made me completely

dotty. I shrieked and shrieked, and danced in my bare feet, and Father, looking awkward and

hairy in nothing but a short gray army shirt, glared down at me like a mountain out for

murder. I think it must have been then that I realized he was jealous too. And there stood

Mother in her nightdress, looking as if her heart was broken between us. I hoped she felt as

she looked. It seemed to me that she deserved it all.

From that morning out my life was a hell. Father and I were enemies, open and avowed. We

conducted a series of skirmishes against one another, he trying to steal my time with Mother

and I his. When she was sitting on my bed, telling me a story, he took to looking for some

pair of old boots which he alleged he had left behind him at the beginning of the war. While

he talked to Mother I played loudly with my toys to show my total lack of concern.

He created a terrible scene one evening when he came in from work and found me at his

box, playing with his regimental badges, Gurkha knives and button sticks. Mother got up and

took the box from me.

"You mustn’t play with Daddy’s toys unless he lets you, Larry," she said severely. "Daddy

doesn’t play with yours."

For some reason Father looked at her as if she had struck him and then turned away with a

scowl. "Those are not toys," he growled, taking down the box again to see had I lifted

anything. "Some of those curios are very rare and valuable."

But as time went on I saw more and more how he managed to alienate Mother and me. What

made it worse was that I couldn’t grasp his method or see what attraction he had for Mother.

In every possible way he was less winning than I. He had a common accent and made

noises at his tea. I thought for a while that it might be the newspapers she was interested in,

so I made up bits of news of my own to read to her. Then I thought it might be the smoking,

which I personally thought attractive, and took his pipes and went round the house dribbling

into them till he caught me. I even made noises at my tea, but Mother only told me I was

disgusting. It all seemed to hinge round that unhealthy habit of sleeping together, so I made a

point of dropping into their bedroom and nosing round, talking to myself, so that they wouldn’t

know I was watching them, but they were never up to anything that I could see. In the end it

beat me. It seemed to depend on being grown-up and giving people rings, and I realized I’d

have to wait. But at the same time I wanted him to see that I was only waiting, not giving up

the fight.

One evening when he was being particularly obnoxious, chattering away well above my

head, I let him have it.

"Mummy," I said, "do you know what I’m going to do when I grow up?"

"No, dear," she replied. "What?"

"I’m going to marry you," I said quietly.

Father gave a great guffaw out of him, but he didn’t take me in. I knew it must only be

pretence.

And Mother, in spite of everything, was pleased. I felt she was probably relieved to know that

one day Father’s hold on her would be broken.

"Won’t that be nice?" she said with a smile.

"It’ll be very nice," I said confidently. "Because we’re going to have lots and lots of babies."

"That’s right, dear," she said placidly. "I think we’ll have one soon, and then you’ll have plenty

of company."

I was no end pleased about that because it showed that in spite of the way she gave in to

Father she still considered my wishes. Besides, it would put the Geneys in their place. It

didn’t turn out like that, though. To begin with, she was very preoccupied – I supposed about

where she would get the seventeen and six – and though Father took to staying out late in

the evenings it did me no particular good. She stopped taking me for walks, became as

touchy as blazes, and smacked me for nothing at all. Sometimes I wished I’d never

mentioned the confounded baby – I seemed to have a genius for bringing calamity on myself.

And calamity it was! Sonny arrived in the most appalling hulla-baloo – even that much he

couldn’t do without a fuss – and from the first moment I disliked him. He was a difficult child –

so far as I was concerned he was always difficult – and demanded far too much attention.

Mother was simply silly about him, and couldn’t see when he was only showing off. As

company he was worse than useless. He slept all day, and I had to go round the house on

tiptoe to avoid waking him. It wasn’t any longer a question of not waking Father. The slogan

now was "Don’t-wake-Sonny!" I couldn’t understand why the child wouldn’t sleep at the

proper time, so whenever Mother’s back was turned I woke him. Sometimes to keep him

awake I pinched him as well. Mother caught me at it one day and gave me a most unmerciful

flaking.

One evening, when Father was coming in from work, I was playing trains in the front garden.

I let on not to notice him; instead, I pretended to be talking to myself, and said in a loud voice:

"If another bloody baby comes into this house, I’m going out."

Father stopped dead and looked at me over his shoulder. "What’s that you said?" he asked

sternly.

""I was only talking to myself," I replied, trying to conceal my panic. "It’s private."

He turned and went in without a word.

Mind you, I intended it as a solemn warning, but its effect was quite different. Father started

being quite nice to me. I could understand that, of course. Mother was quite sickening about

Sonny. Even at mealtimes she’d get up and gawk at him in the cradle with an idiotic smile,

and tell Father to do the same. He was always polite about it, but he looked so puzzled you

could see he didn’t know what she was talking about. He complained of the way Sonny cried

at night, but she only got cross and said that Sonny never cried except when there was

something up with him – which was a flaming lie, because Sonny never had anything up with

him, and only cried for attention. It was really painful to see how simpleminded she was.

Father wasn’t attractive, but he had a fine intelligence. He saw through Sonny, and now he

knew that I saw through him as well. One night I woke with a start. There was someone

beside me in the bed. For one wild moment I felt sure it must be Mother, having come to her

senses and left Father for good, but then I heard Sonny in convulsions in the next room, and

Mother saying: "There! There! There!" and I knew it wasn’t she. It was Father. He was lying

beside me, wide-awake, breathing hard and apparently as mad as hell. After a while it came

to me what he was mad about. It was his turn now. After turning me out of the big bed, he

had been turned out himself. Mother had no consideration now for anyone but that poisonous

pup, Sonny.

I couldn’t help feeling sorry for Father. I had been through it all myself, and even at that age I

was magnanimous. I began to stroke him down and say: "There! There!"

He wasn’t exactly responsive. "Aren’t you asleep either?" he snarled.

"Ah, come on and put your arm around us, can’t you?" I said, and he did, in a sort of way.

Gingerly, I suppose, is how you’d describe it. He was very bony but better than nothing.

At Christmas he went out of his way to buy me a really nice model railway.

No comments:

Post a Comment